I feel like I have to credit the beginning of my transition at least partly to Vogue's 'Extreme Beauty' series on YouTube. It was the first Covid lockdown in the UK, in 2020. I had just finished my A-Levels and was due to move out of my childhood home as I would be starting university in a few months. In the meantime, stuck indoors, I watched absolutely anything on YouTube. At that time, I saw Juno Birch's 'Extreme Beauty' video. The 'Extreme Beauty' videos basically showcase public personalities with more outlandish signature looks sitting down and detailing their make-up routines, influences, and upbringings to the camera- they're a lot like 'get ready with me' videos.

Juno Birch in her 'Extreme Beauty' video

Apart from the fact that many of the people featured in the videos talk about taking inspiration from horror pop-culture for their appearances, the series is largely unrelated to horror and I can't label it under the genre for obvious reasons. However, I feel I must include it in my horror-based project because it eventually inspired a period in my own self-expression where I was experimenting with make-up for the express purpose of looking disturbing and off-putting.

The people who have been featured in Vogue's 'Extreme Beauty' series, in order, are:

- Hannah Dalton and Steven Bhaskaran (better known as the duo Fecal Matter (@matieresfecales on Instagram))

- Juno Birch (@junobirch)

- Jazmin Bean (@jazminbean)

- Salvia (@salvia001011)

- Johannes Jaruraak (better known as the drag artist Hungry (@isshehungry))

- Sgaire Wood (@sgairewood)

- Parma Ham (@parma.ham)

- Leo Monira (previously ‘Spooky Kid’ (@leomonira))

- Chadd Curry (better known as dahc Dermur VIII (@dahc_dermur_viii))

- Jenkin van Zyl (@jenkinvanzyl)

- The drag artist Charity Kase (@charitykase)

- Michael Moon (@michaelmoon.vision)

- and Princess Gollum (@princessgollum)

A photo shared on the Instagram page of Fecal Matter (@matieresfecales)

Something shared amongst most of the video subjects is their own specific idea of beauty being consistently painful. The subjects will often remark - as they put in sclera contact lenses or use superglue to hold prostheses - that it hurts, but that they don't mind because the end result will be satisfying enough to them that any pain they go through will be worth it.

The everyday impracticality of their make-up and outfits is always highlighted in a segment at the end, a portion of the video dedicated to the subject going out in public to show off their look and do something mundane. These are my favourite parts of the videos. There's something so charming about Juno Birch in her alien woman drag attire shopping at Tesco, Salvia cycling down country roads in huge Pleaser boots, or Hungry eating a meal alone in a fancy restaurant wearing a bug-like face piece. This is the sort of magical realism that I am always drawn to. I hope it doesn't come across as derogatory to call these videos 'magical realism' (pertaining to average, realistic settings punctuated by striking fantasy elements). I know that the subjects are just average people, but since they strive, with their looks, to be otherworldly, and the videos highlight their extraordinary-ness (is that a word?) in contrast to everyday living, I think it's a fair definition. Just know that I mean it with love, as seeing something unusual or artistic in an otherwise boring place is something that makes me intensely happy. Now, onto Salvia.

Salvia in 'Inside Salvia's Extreme Beauty Routine | Vogue' on YouTube

"If I'm dressed and I've got my make-up on, sometimes just living and going out and interacting with the world can be its own performance and its own art piece because it can be so theatrical and beautiful," - Salvia.

Salvia is an artist and musician influenced by (in her own words) Alexander McQueen, Leigh Bowery, and Lady Gaga music videos. In her Vogue video, she begins by supergluing clear tubes from her nose to her forehead. She then uses foundation and powder to make herself paper white. She pays particular attention to her eyes by shadowing her eyebags and the outer corners of her browbone, before colouring the inner corners of her eyes red. She uses white eyeliner on her lips before shadowing the centre and outer edges of her mouth, as well as the points where the tubes protrude from her forehead. She puts in fully red contact lenses and wears a beige wig. The overall result, if I had to describe it, is medical, but faun-like. 'Faun grown in a lab from human DNA'.

In her video, she expresses the desire for an 'alien' face and explains that her look is a continuation of art she made as a teenager - paintings of humans with impossibly futuristic body modifications. One of the things she talks about that really stuck with me was that most of her looks are a way to conquer her own personal societal fears and overcome the trauma of her upbringing. Many other subjects of Vogue's 'Extreme Beauty' videos express that being uniquely themselves, visually, has helped them grow and become more realised. My biggest fear at the time of watching these videos was that I would never be myself, or find a 'myself' to be. I worried that I'd never be able to contribute anything to the world. I hadn't yet realised I was trans, so my overall displeasure with my appearance manifested itself as the thought that I would be happier if I had an aura, or if I was a walking mood board. I wanted someone to be able to look at me and know all that I knew, or was interested in. In short, I felt boring and nothing, and the sort of internal/external incongruence that is rife in trans narratives was me being afraid that if I died as I was, then everything in my head would die with me. I wanted everything that was me out of my head for all to see, and thought that a good step toward combatting these feelings would be experimentation with make-up to embody my interests (of course, with heavy inspiration from these videos).

Various photos from Salvia's Instagram (@salvia001011)

I watched more to try and think up what I should look like. Another one of my favourites in Vogue’s 'Extreme Beauty' series was the video featuring the artist then known as Spooky Kid.

Leo Monira outlined in his Vogue video that he started going by the moniker 'Spooky Kid' after receiving comparisons to Marilyn Manson when he was in high school, subsequently discovering the band 'Marilyn Manson and the Spooky Kids'. However, there is now no mention of this moniker on Monira's Instagram page, and he seems to have rebranded (potentially due to Manson's abuse allegations), so I will not refer to him by it.

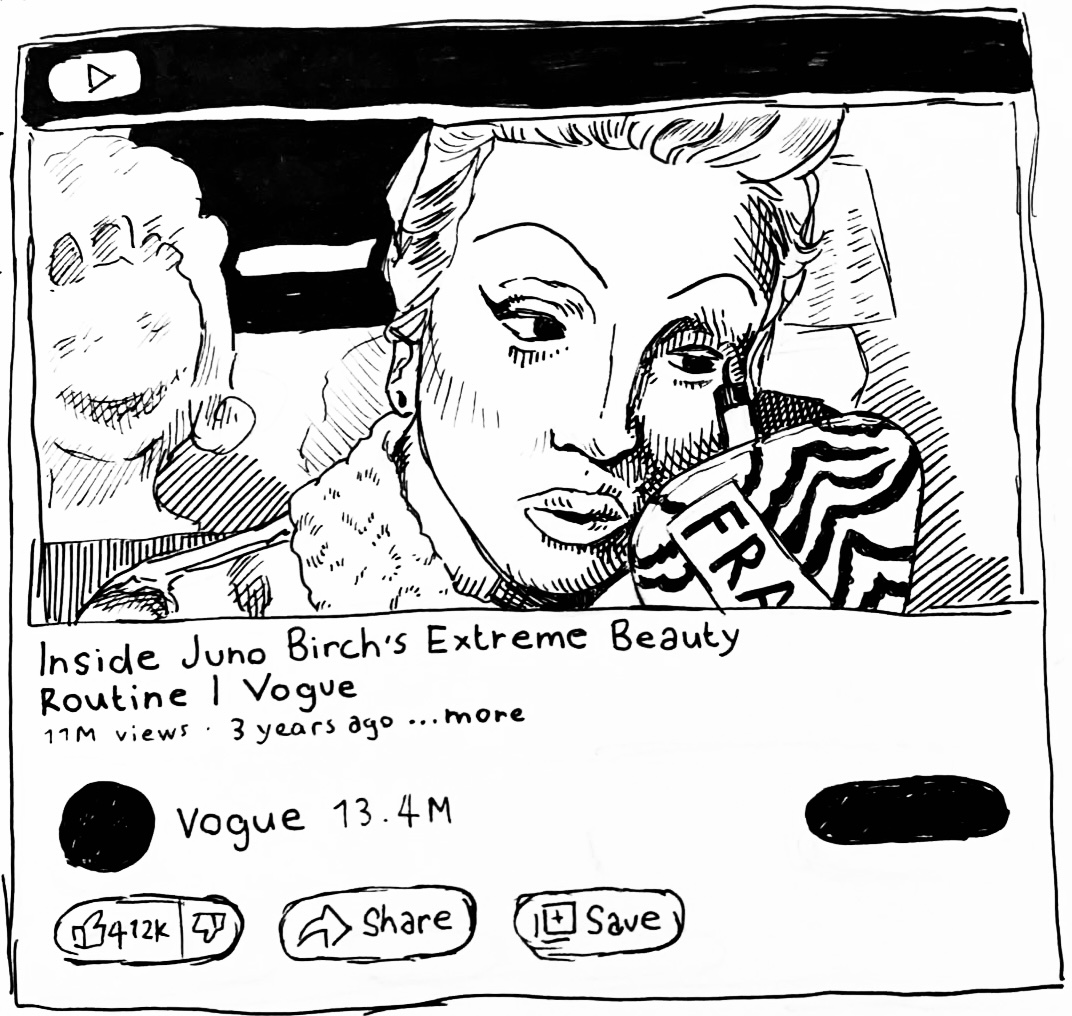

Anyway, Monira is the reason why, to this day, if I doodle myself, I will draw my hair as if I have devil horns. Monira himself only has two strands of hair (the rest being clean shaven), which he often uses gel to spike up.

The thumbnail image for 'Inside Spooky Kid's Extreme Beauty Routine | Vogue'

In his Vogue video, Monira covers his face in primer, and then white foundation. He uses red eyeshadow to give himself a 'tired' look, then uses a combination of pink and yellow blush on his cheeks, all the way up to his brow bone, also adding highlighter on his cheekbones. He creates a 'futuristic' spiky lip shape with black liner, and then covers his face at random with dots of red and black eyeshadow, adding a dot of white eyeliner at the centre to create the illusion of having pus-filled zits. He flattens his tufts of hair to his forehead with water and wax and then puts in mismatched contact lenses. One is a combination of two lenses, giving the appearance of having a red sclera and a white iris, whereas the other is just a red sclera. Lastly, he puts on oversized paper-y white eyelashes before putting on his outfit.

"It's more like I'm creating a character where I can project what I have inside myself (...) express what you have inside yourself and you can't deal with." - Leo Monira in 'Inside Spooky Kid's Extreme Beauty Routine | Vogue'.

Various photos from Leo Monira's Instagram (@leomonira)

What I loved the most about Monira's look, what I parroted endlessly when I eventually used make-up for myself, was the counterintuitive painting on of what is usually covered up with make-up. Things like the zits and dark circles under the eyes. The traditionally ugly. It is perhaps surface level to point out that the idea of using make-up to make yourself look 'worse' instead of more conventionally attractive is unusual, but that's what I liked as with it came the idea that there wasn't the pressure to do the make-up perfect. With no right way to look bad, there was no pressure for it to be good, as any embarrassing mishaps could be seen as purposeful. This was comforting to me as a first-time user of make-up.

The walls of Monira's living space are covered in paintings. He talks about drawing monsters and witches as a child. So similar, Jazmin Bean in 'Inside Jazmin Bean's Extreme Beauty Routine | Vogue' holds up a copy of the Tim Burton illustrated 'The Melancholy Death of Oyster Boy and Other Stories' and talks about how they used to make clay models of the characters, and that their mother used to compare their appearance to one of the illustrations. It's always the children who are interested in the unusual: common amongst all the Vogue videos is the narrative of being outcasted at a young age, with the phrases 'small town' and 'closed-minded' (read; 'religious') being used a lot. Overall, overcoming is the name of the narrative, almost synonymous with queer narratives. Coming into oneself against the odds of your ubringing, however played up this is in the Vogue videos (I couldn't possibly say), is of course what I latched onto at a time when I was about to move away from home.

As I write this I fear I am writing a lot but saying very little, and struggle with the idea that I am boring and that this project is already becoming too planned or artificial, which was not my original intention. I have nothing constructive to add apart from that these people looked a certain way, and that later I will talk about how I copied them to no end. I will use a lot of words to fill up a webpage in the hopes that it looks like I put effort into at least something. Rewatching the Vogue videos, I am reminded why I began this project in the first place: paranoia about covert surveillance. Different mouth, the same words. It's funny the way in which these things are so often cyclical. A throwaway line in something I watched years ago echoes into a present fear. Not even my delusions are original.

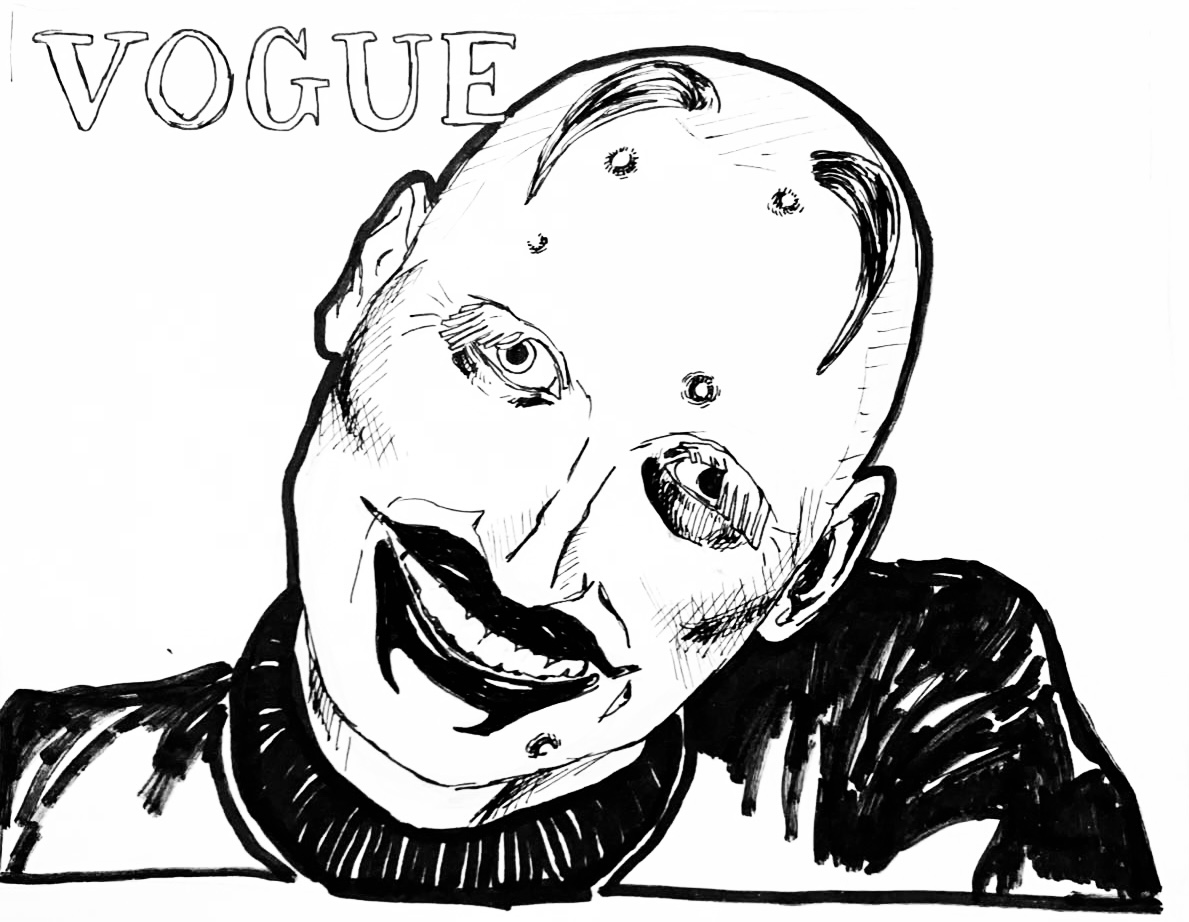

Johannes 'Hungry' Jaruraak in his Vogue video.

"Back in school, I briefly did some research on camera surveillance and how you could prevent it or how you could confuse the cameras and started working with the idea of hiding the nose. I noticed that the earliest - when none of the face filters would work on my face or when cameras didn't really see my face anymore." - Hungry in 'Inside Hungry's Extreme Beauty Routine | Vogue'

Why say something when someone else can say it so much better?

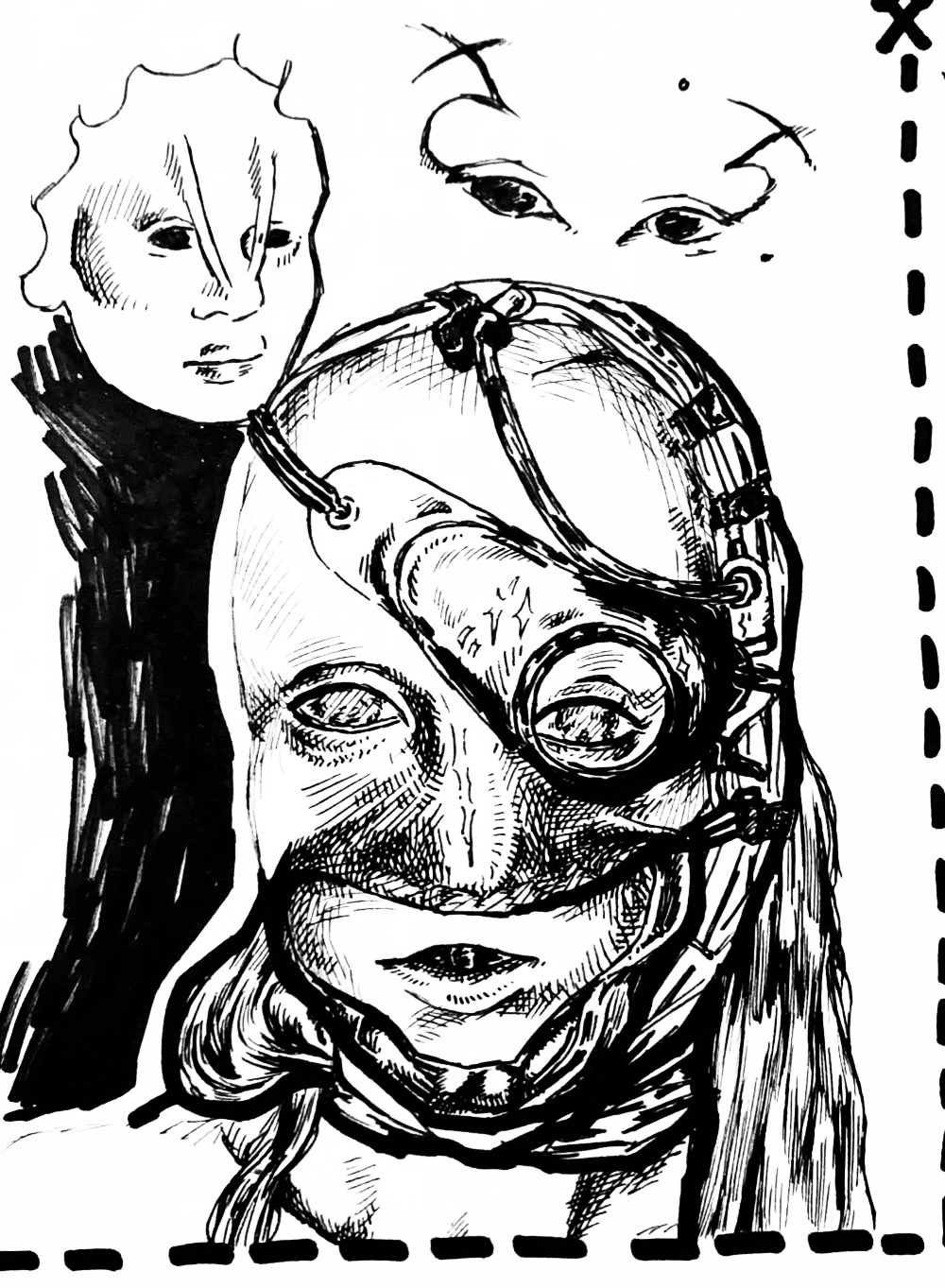

Biometrics tend to try and pinpoint facial features like the nose, mouth, and eyes, and then measure the distance between each. For something like unlocking a phone with Face ID, these measurements are compared to the pre-existing measurements you have given your phone. The obvious way to evade recognition and comparison to pre-scanned faces is the distortion of the nose, mouth, and eyes: to make like Hungry and elongate the eyes into spikes, or to copy Jazmin Bean and strike out for removing a human nose shape.

I find it interesting that having a 'non-human' face evades pattern recognition in biometrics, but seeing someone in extreme alternative make-up promotes a queer recognition. The subjects of the Vogue videos talk about finding community at extreme parties, and that meeting others on the scene who look different to them but extreme in the same way is gratifying. The queer paranoia community, attempting to be exempt from the attention of the human recognition, creating a family out of it, in fact. The rejection of the mainstream which, so often before the fact, rejects what it does not understand. Facial horror to queer aesthetic, therefore, does not seem a leap.